Tackling Strength

Is rugby now too dangerous for children? That was the title and question posed by Tim Lewis back in 2014 in his article in The Observer found here. If you have been following the rugby injuries story lines over the past 5 years you will have read many similar articles and probably joined in on many discussions. The problem is that this excellent article is over 3 years old now and have things changed? 3 weeks ago ex England fly half Rob Andrew, and ex Director of Elite/Professional Rugby at the RFU, didn’t think so. In a radio interview concerning young player welfare he concluded that within teenage schools rugby, and particularly at those traditional schools with long histories of rugby development, there is still a huge problem… that being the prioritisation of size over skill. If you read around the topic you will find the same associations and language.

Size: teenage strength and conditioning, testosterone, protein shakes, supplements, results based culture, commercial pressure, ease of access to effective unregulated “sports science”… and size culture.

Skill: bulldozed, over-ridden, small frame, unfavourable rule changes, disparity, technically gifted but physically underpowered.

In my opinion there is much more to this than just the list above. Strength and Conditioning, and protein shakes don’t make a culture… they are just a part of it. And we shouldn’t be surprised that major players in the both the rugby and medical landscape feel that progress is slow… cultural change is always a crawler, especially if commercial factors underpin, or interfere with potential change. In professional rugby, right now, size sells, and the club owners and boardrooms add their own language to the size debate; profit, revenue, product, sales, sponsorship, deals and projections. When it comes to business, big is usually best.

But the “size over skill” phenomenon is not just a rugby problem. It’s been talked of in football, tennis, netball and pretty much all field and court sports for many years. National governing bodies, the coaching community, and athlete development specialists have been wrestling with it for years. But rugby cannot hide behind the shared nature of the problem… rugby has a problem, and the combative and collision based nature of the sport accentuates it. The good news is that there are folks trying to do something about it from various perspectives.

You have proper scientist types like Nutton, Hamilton and Hutchison et al with their research paper “Variation in physical development in schoolboy rugby players” in the British Medical Journal found here. They discuss the concept of maturity testing preventing physical mismatch and injury … lets call it size groups rather than age groups.

You get a public health professor, and mother of a thoroughly battered rugby playing son, who decided to investigate injury incidence within schools rugby and became author of the book “Tackling Rugby: what every parent should know”. You will find Alyson Pollock’s website here. I have also heard her described as “that woman who wants to ban rugby tackling at school”. Well she definitely is that woman but I don’t think it contributes to the debate to describe her in that way. Better to read her blog and make your own mind up… it’s not an easy debate, I’m still making my own mind up… but she is a hugely legitimate voice to be heard.

More importantly you get the NGB’s of rugby themselves. There are good people within these organisations and within their sports science, medical and coaching departments, working hard to address this issue. You will find this resource on the IRFU website, and a comprehensive England RFU policy statement pdf here (RFU-Position-Statement-on-Strength.pdf), which I urge you to read. As you would expect the stance taken by the rugby NGB’s supports the implementation of youth strength training, and the majority of their resources expand upon how to do this strength training safely and appropriately. In a way this could be interpreted as making sure the stress of the strength training itself does not create injury, rather than the results that the body composition and power increases have when out on the field. I personally don’t think that interpretation is fair. And this is the reason why:

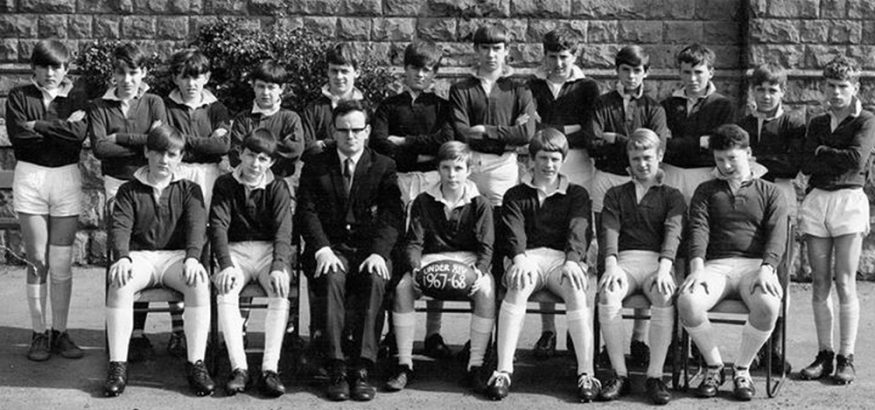

So this is a comparative image that many folks will use when debating this issue. Above we have a free flowing Will Carling struggling to fill out his kit. Below we have two statuesque teenagers who have successfully been signed from school to a professional academy, and their kit is struggling to contain their muscles. There’s your problem right there. Wrong. It’s fake news…. lazy journalism. The lad on the right there hasn’t got a neck, biceps and mega quads like that without lifting some weights… and I am guessing he did it with structure and an awful lot of personal time and effort. Now I am absolutely sure that he has generously shared the results of his efforts with a number of opposing schoolboys during his player development , and they may have the bruises to show for it. But he hasn’t really done it for the now, it has been part of his plan for the future. His next step up is to a professional academy where all of his training partners and opposition also struggle to get into their kits. He has taken advantage of a testosterone filled window of opportunity to prepare his body for this step up. Put frankly, there may be a physical risk involved in playing rugby, but this risk significantly increases if you are not physically adapted (strength trained) to cope with the physical risk. It would be irresponsible to be inadequately prepared.

So what is the take home on this one? Well for me the whole rugby thing is a typical example of a “top down” media tempting story. By “top down” I mean it is highlighted most at elite level… highly specialised athletes playing at the ultra elite end of a sport that requires specific physical adaptation… as indeed many sports do. It is not a problem that is getting blown out of proportion, but it may be one that gets proportionally more media time that it deserves… specifically when compared to a more glaring and universal problem. What is that? Well the bigger problem is that our children are not strong enough. Not the rugby playing ones… just loads of the rest of them. They aren’t strong enough. Some may even be weak. Weak kids. There you go… I have gone and said it. Cue social media backlash and negative language association twitter lashing. But its true… it’s not just me rattling your cage. Listen to Dr Mark Tremblay, of Ottawa University. He studies the health of Canada’s snow balling, skating, climbing, skiing, tree chopping, moose wrestling children. He says, “Statistically and meaningfully we are not doing so well. It is profound to summarize that a 12 year old is taller, heavier, rounder, weaker, less flexible and less aerobically fit than a generation ago.” Back in the UK at Essex University they studied 309 ten year olds in 1998 and another 315 in 2008. Over the 10 year period, they found sit up max declined by 27%, arm strength max had declined by 26%, and if you hung them all on a high bar back in 1998, 1 in 20 of them would drop off, but by 2008 1 in 10 would drop off.

A positive thing to come out of the research done around youth rugby strength training is the clear findings that strength training for children isn’t developmentally “dangerous”. It doesn’t damage growth plates, or over stress bone, or stunt hormones, or shorten muscle groups, or give girls beards. It can be easily adapted and applied across age groups, it’s inexpensive, it can be made fun and un-threatening, it is skills light and uncomplicated, and it works … the children that take part can measure their improvements easily. Of course it is nice to apply your hard earned strength gains in some form of activity, but it doesn’t have to be measured in tackles made, or goals scored… simply putting an extra couple of press-ups on your one minute max can give a valuable sense of achievement.

Our children live in a society that has engineered movement out of their everyday lives, let alone strength. The majority of children are more at risk of thumb RSI rather than crunching tackles. Rugby may have a “minority” problem with the consequences of specific strength training and it must ensure that it continues to be addressed. But society may soon have a “majority” problem with the robustness of it’s younger members, and strength training is how to address it.

Comments are closed.